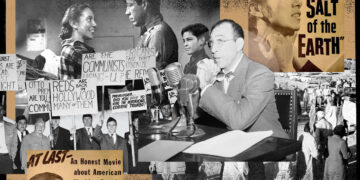

For over a decade beginning in 1947, the anti-Communist witch hunt that was the Hollywood Blacklist ruined careers, families, and lives. Anyone who came to the attention of the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) and who refused to name names or publicly denounce communism was put on the proverbial list, the notoriety of which stripped them of their ability for gainful employment. No Hollywood player wanted to be guilty by association.

Director Herbert Biberman was named in the earliest, most infamous wave of HUAC victims known as “The Hollywood 10.” He was sentenced to jail for six months for refusing to answer Congress’ question about his communist affiliation. Producer and screenwriter Paul Jarrico was swept up in the second wave and also stayed silent. Soon after screenwriter Michael Wilson won a 1952 Oscar for A Place in the Sun, he was blacklisted for—you guessed it—refusing to cooperate.

Most of the men who were blacklisted either never worked again or struggled to produce work under pseudonyms or outside of the country. But in 1953, these three men took a different path. They decided to form their own production company to make films they were passionate about, movies about “real people and real situations.”

For their first (and only) film, the Independent Productions Corporation (IPC) decided to tell the story of an important social justice movement taking place in New Mexico where a group of mostly Mexican-American mine workers were engaged in a 15-month strike against the Empire Zinc Company.